The Behavioral Economics of Return to Office

A few psychological quirks, and their implications for organizations who want to handle the situation more delicately

In what feels like an inevitable pendulum swing from the remote work experiment, bosses have been running their own return-to-office mandate experiment for a few years now, and researchers have had a chance to study the impacts.

Yuye Ding and Mark (Shuai) Ma from the University of Pittsburgh recently released a clever1 and already-well publicized study, finding that companies in the S&P 500 who instituted return to office mandates experienced decreases in employee satisfaction along with no discernible increase in overall firm performance.

The authors don’t theorize much as to why return to office decreased employee satisfaction. And to be fair, maybe they didn’t need to. It’s obvious right, companies take away something employees liked, they’ll be less happy?

There’s More to this than Carrots and Sticks

If there’s one lesson from behavioral economics, it’s that there’s likely more to the story. Besides, if we don’t understand the “why” of these findings then we’ll be doomed to repeat mistakes.

The Endowment Effect and Loss Aversion

One of the most studied psychological biases describes what happens when people own things: they value them more. For example, researchers created an experiment where half the participants were randomly given a coffee mug, and found that they valued the mug at around twice as much as the control participants who weren’t given one. These findings on the endowment effect never cease to fascinate, and have been replicated numerous times.

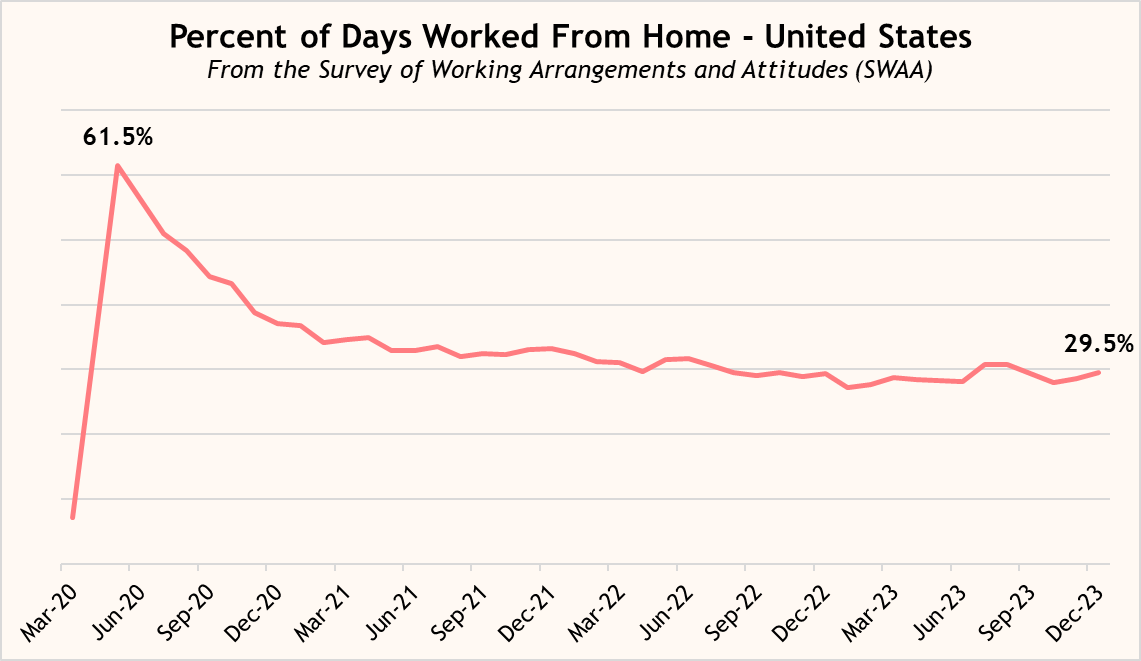

Like college undergrads getting free mugs, a sample (admittedly not so random) of workers suddenly received remote work in 2020, and most recent estimates suggest that days worked from home have stabilized at around 30% for U.S. workers.

If the endowment effect is at play, the implication is that workers may value remote work more now than they did before, for the simple fact that they have it. Speaking of value, data suggests workers do value the ability to work from home at somewhere around 8% of their salaries.

Not only might workers value remote work more because they have it, they may react especially negatively if they lose it. This is due to another well-documented psychological bias that might be running in parallel: loss aversion2, the fact that losses loom larger than gains. A pay raise is good, but not as good as a pay cut is bad. Imagine how an 8% pay cut would feel!

Psychological Contracts

Workers have unwritten expectations about what their employer will provide them and what they will provide in return: psychological contracts. Because these contracts are covert and hard/costly to observe, this means the ground can shift under the feet of leadership without them realizing it, with workers having different expectations now than they did before the pandemic.

Violations, or breaches of psychological contracts are associated with lower job satisfaction, which may be the most direct theory as to why return to office mandates haven’t been a smash hit.

Implications for Decision Making and Work Arrangement Policies

An implication of these three psychological features is that incumbent workers who were endowed with remote work privileges should be thought of as a totally different segment than new potential workers: naturally, people accepting a job with the expectation of a hybrid / in-office arrangement will be much more amenable to it. This opens the door to a much less draconian “soft return-to-office” whereby organizations manage a shift back towards in-person work through a combination of natural turnover and mindful hiring.

The fact that so many organizations are already completely geographically distributed - in part due to remote workers (many of whom moved during the pandemic), but also from offshoring - adds another wrinkle to the question. Because in-person work is costly, it’s crucial to figure out when it is essential, and when it is not. As Microsoft research paints clearly: it’s about the moments that matter. Figuring out which pivotal talent need to get together for what work will generally lead to more informed policies than blanket mandates, because a problem well understood is a problem half solved.

Raising the bar

When it comes to bringing folks back, if making employees whole amounts to an ~8% pay raise, then clearly organizations are going to have to level up their game to find the equilibrium. One actionable tip from the endowment effect literature is that when people are endowed with something, they generally under-weigh associated opportunity costs. Put into other words / practice: the benefits of in-person work may not be as psychologically salient to folks who’ve grown accustomed to remote work. Creating good reasons for folks to come in and actively reminding them of those reasons may be needed to meet the “what’s in it for me”.

The researchers made good use of publicly available data on S&P 500 companies, including public filings, Glassdoor reviews from employees, and news articles identifying which companies instituted return to office mandates. If you’re a people analytics nerd you’ll be interested to read about the difference-in-differences design they used to estimate the effect of return to office mandates on employee attitudes. Yes, the parallel trends assumption held!

*Astute readers may notice the apparent similarity between the endowment effect and loss aversion. While there has been some controversy over the subject, at least one recent review of the literature suggests there are more foundational cognitive mechanisms at play which may explain the endowment effect.